“Our sons were both diagnosed with ADHD by kindergarten. More than just dealing with the disciplinary and academic issues at school, my husband and I struggled to maintain a productive and nurturing household with the kids having regular meltdowns and outbursts. Our ability to connect with them became compromised. We were at our wits’ end considering medications and home school. We agonized over the long-term repercussions of both of those choices. We turned inward and analyzed our habits and routines. One thing we noticed with both the boys was that a strict routine in the mornings and in the evenings seemed to help and that physical interventions (rather than reasoning or time-outs) worked best to correct behavioral problems – getting them outside, running them around, engaging them in a physical activity. There were particularly frenetic times when we would take them to the track at the local middle school and have them run laps. The more we intervened in that way, the fewer the outbursts and behavior issues and ironically, the better they’d sleep; but we were concerned that they would start seeing exercise as a punishment and decided to take a different approach.

We figured if we were all involved in a healthy movement regimen, it would be more of a lifestyle than a penalty. We became a running family. We started with an early morning jog around our neighborhood before school and work – all of us, the whole family. At ages 8 and 5, our boys loved it. When they got home from school in the afternoons after snack and before homework, we jogged again. The rest of the evening, we tightly structured homework, dinner, bath and bed. We even ran on the weekends on the same schedule around extra-curricular activities. The results were immediate. Behavior at home and at school improved drastically, our parent-teacher conferences became a pleasure, and even their little personalities shifted from quick emotion to much more flexibility and understanding. It has changed our family for the better. Not only are our kids not on stimulants or anti-depressants, we all feel fit and healthy and we get to do it together every day.”

I find this case and others like it fascinating. How can such a simple lifestyle change make such an impact on ADHD outcome? It turns out, there are a number of reasons.

ADHD, with its many subtypes, affects the lives of around 10% of American kids. Inattentive type, hyperactive/impulsive type (rare) and the combined type all have their own clinical features and findings but kids with ADHD, in general, may have problems with controlling impulses, concentrating, focusing, sleeping, sitting still, paying attention and listening. Inappropriate emotional outbursts can present and often anger is associated.

A diagnosis typically leads to a trial of one of several medications to "wake the brain up" to increase concentration and focus. Probably the most popular drugs for ADHD today are stimulants such as amphetamine-salts (Adderall) and methylphenidate (Ritalin) – both work to increase norepinephrine and dopamine activity in the brain. Atomoxetine (Strattera) increases serotonin and norepinephrine activity in the brain. All of these drugs excite the brain and as such have similar common side effects even though each one has a unique mechanism of action.

What’s going on in the body and the brain with ADHD?

Daydream-State Brain Waves

First, we have learned from EEG studies that there may be different brain wave patterns in different subtypes of ADHD. The theme, however, seems to be a higher ratio of theta to beta waves than in a non-ADHD brain. [1] Theta waves are normally higher during sleep just before waking and beta waves are highest when we're concentrating and processing information. So, a child with ADHD is literally asleep at the wheel when he or she is expected to concentrate and function at school.

Low Sympathetic Tone

Second, urinary phenethylamine (PEA) tends to be low in kids with untreated ADHD. [2] As a modulator of norepinephrine transmission in the central nervous system, it enhances sympathetic tone. A normal sympathetic tone gives us the baseline function that enables our bodies to appropriately react and respond to stressors and provides the terrain for brain activity, wakefulness, and concentration. This may be an isolated finding but more often than not, we will see this low urinary PEA in concert with a low urinary dopamine in patients with ADHD. In cases where urinary dopamine is within the normal range, it is most often low compared to urinary serotonin in the same specimen. What is this telling us? Urinary dopamine (along with norepinephrine, discussed below) and PEA give us information about sympathetic tone and when it's low, it explains much of the symptomatology associated with ADHD. The result of effective treatment, whether conventional or alternative, is to raise dopamine, serotonin and PEA levels in the urine.

Urinary dopamine and PEA give us information about sympathetic tone and when it’s low, it explains much of the symptomatology associated with ADHD |

Abnormal Stress Response

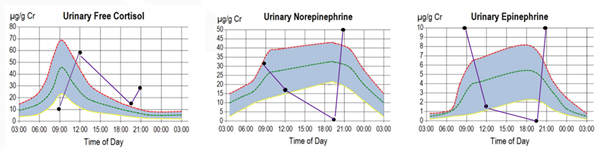

Third, the urinary diurnal rhythms of free cortisol, norepinephrine and epinephrine are often dysfunctional in ADHD, and HPA axis dysfunction is common in the inattentive type. [3] Cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine are all normally released from the adrenal glands at a baseline level and in response to all sorts of stressors. Cortisol production responds to signaling from the pituitary gland and the norepinephrine in the urine comes straight from the sympathetic nervous system (well, 80% of it with the rest from adrenal production) and positively correlates with our sympathetic tone. Epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) in the urine is the direct result of adrenal production and should be thought of as an adrenal stress indicator. When these diurnal markers are out of rhythm, symptoms such as anxiety, nervousness, insomnia, and that "over-tired" burned out emotional feeling start to emerge. Typically, a child with a combined-type ADHD will show elevated or normal pooled cortisol levels with an abnormal diurnal rhythm, low norepinephrine (or low by comparison) with an inverted diurnal rhythm, and a high pooled epinephrine with an inverted diurnal curve.

An example of the abnormal urinary circadian curves often seen in a child with ADHD and an anxiety component is shown in the purple lines on the graphs below (keep in mind the blue-shaded area would be considered "in the normal range" and represents the shape of the normal expected curve):

Hyperexcitation & Neurotoxicity

Finally, urinary glutamate may be elevated alongside a functionally low urinary GABA in kids with ADHD who have the perfect storm of diet and a susceptible biochemistry. Glutamate is one of the major on-switches in the brain and its rise in the body may be either representing a compensatory mechanism in ADHD to counter a low sympathetic tone, or simply the result of genetic mutations leading to glutamatergic dysfunction. In either case, taking steps to protect the brain from neurotoxicity as a result of overexcitation is key to good clinical outcomes. In the body’s infinite wisdom, glutamate’s inhibitory counterpart, GABA, is synthesized from glutamate and it’s an important reminder that absolute levels of urinary neurotransmitters are probably less important than the balance between them. Outside the brain, GABA is synthesized in the adrenal glands and acts as the gatekeeper of norepinephrine and epinephrine synthesis, an important modulator of the stress response. Levels in the urine mainly reflect that adrenal contribution and so as much as it's important to assess the balance with glutamate, assessing for its balance with norepinephrine and epinephrine may even be more telling.

Drop down and give me 20!

It turns out, there is a therapy after all that can rouse the ADHD brain and raise PEA and norepinephrine levels to improve sympathetic tone and it’s not administered in a pill. It’s exercise! For those who need more than common sense to get behind this treatment option, physical activity for ADHD has also been well studied. A recent study that looked at kids with ADHD given an 8-week yoga intervention twice a week for 40 minutes found that the kids in the yoga group significantly improved from baseline on cognitive inhibition and attention tests. [4] The FITKids Trial in 2014 randomized kids between the ages of 7 and 9 to a 9-month afterschool physical activity regimen or a wait-list. They found that the kids that engaged in the physical activity program performed significantly better on attention and cognitive inhibition testing than their wait-listed counterparts. [5]

The take-home is this:

- Exercise changes brain waves and improves cognitive inhibition in kids with ADHD.[6] [7] [8]

- Exercise improves sympathetic tone. [9] [10]

- Exercise influences glutamate and GABA balance in the brain and in the body. [11] [12]

Exercise is not a punishment! To teach our kids the power of it is to give them a gift for life. For kids with ADHD, you could be empowering them to modulate their moods and impulses with a tool they can control.

I hope that parents searching for answers other than supplements and medications for their kids with ADHD, or who seek adjunct lifestyle therapies for their kids already being managed on medications, consider talking to their pediatricians about incorporating physical activity into the regimen. There are lots of options. And perhaps even better, like the family's story featured here, find a way to involve everyone in daily physical activity because half the battle is setting a good example. After all, exercise rules for supporting cardiovascular, mental, immune, and endocrine health – and what's more, it raises the levels of hormones (like oxytocin) and neurotransmitters in the body that make us feel closer and more connected. It’s exactly the physical help families need to work together to weather through some of the more difficult challenges of ADHD. [13] [14] [15]

Related Resources

- Blog: Clinical Utility of Urinary Neurotransmitter Testing

- Download: Neurotransmitter Testing Patient Handout

References

[1] Clin EEG Neurosci. 2017 Jan;48(1):20-32. Epub 2016 May 11. Quantitative EEG in Children and Adults With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Comparison of Absolute and Relative Power Spectra and Theta/Beta Ratio. Markovska-Simoska S1, Pop-Jordanova N2.

[2] No To Hattatsu. 2002 May;34(3):243-8. Decreased beta-phenylethylamine in urine of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autistic disorder. Kusaga A1.

[3] Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2008 Mar;39(1):27-38. Epub 2007 Jun 13. The stress response in adolescents with inattentive type ADHD symptoms. Randazzo WT1, Dockray S, Susman EJ.

[4] PeerJ. 2017 Jan 12;5:e2883. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2883. eCollection 2017. Effects of an 8-week yoga program on sustained attention and discrimination function in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Chou CC1, Huang CJ1.

[5] Pediatrics. September 2014. Effects of the FITKids Randomized Controlled Trial on Executive Control and Brain Function. Charles H. Hillman, et al.

[6] Exp Brain Res. 2015 Apr;233(4):1069-78. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4182-8. Epub 2014 Dec 24. The relationship between aerobic fitness and neural oscillations during visuo-spatial attention in young adults. Wang CH1, Liang WK, Tseng P, Muggleton NG, Juan CH, Tsai CL.

[7] Neural Plast. 2015;2015:717312. doi: 10.1155/2015/717312. Epub 2015 Feb 10. Effects of physical exercise on individual resting state EEG alpha peak frequency. Gutmann B1, Mierau A1, Hülsdünker T1, Hildebrand C1, Przyklenk A1, Hollmann W2, Strüder HK1.

[8] Int J Dev Neurosci. 2014 May;34:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.12.009. Epub 2014 Jan 8. Acute exercise induces cortical inhibition and reduces arousal in response to visual stimulation in young children. Mierau A1, Hülsdünker T2, Mierau J2, Hense A2, Hense J2, Strüder HK2.

[9] Pediatr Res. 2003 May;53(5):756-61. Epub 2003 Mar 5. Catecholamine response to exercise in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Wigal SB1, Nemet D, Swanson JM, Regino R, Trampush J, Ziegler MG, Cooper DM.

[10] Behav Neurosci. 2015 Jun;129(3):361-7. doi: 10.1037/bne0000054. Physical exercise affects attentional orienting behavior through noradrenergic mechanisms. Robinson AM1, Buttolph T2, Green JT2, Bucci DJ1.

[11] J Altern Complement Med. 2010 Nov;16(11):1145-52. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0007. Epub 2010 Aug 19. Effects of yoga versus walking on mood, anxiety, and brain GABA levels: a randomized controlled MRS study. Streeter CC1, Whitfield TH, Owen L, Rein T, Karri SK, Yakhkind A, Perlmutter R, Prescot A, Renshaw PF, Ciraulo DA, Jensen JE.

[12] Applied Physiology , Nutrition and Metabolism. 2106. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0033. Exercise increases mitochondrial glutamate oxidation in the mouse cerebral cortex. Herbst EAF, Holloway GP.

[13] Psychiatry Res. 2015 Aug 30;228(3):746-51. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.029. Epub 2015 Jun 15. Decreased levels of serum oxytocin in pediatric patients with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Sasaki T1, et al.

[14] Eur J Endocrinol. 2008 Dec;159(6):729-37. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0064. Epub 2008 Sep 15. Acute changes in endocrine and fluid balance markers during high-intensity, steady-state, and prolonged endurance running: unexpected increases in oxytocin and brain natriuretic peptide during exercise. Hew-Butler T1, Noakes TD, Soldin SJ, Verbalis JG.

[15] Eur J Sport Sci. 2017 Apr;17(3):343-350. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2016.1260641. Epub 2016 Dec 7. The importance of cohesion and enjoyment for the fitness improvement of 8-10-year-old children participating in a team and individual sport school-based physical activity intervention. Elbe AM1, Wikman JM1, Zheng M1, Larsen MN1, Nielsen G1, Krustrup P2,3.