It feels like winter is officially looming now that we’ve all turned our clocks back and the days are getting shorter. In the Pacific Northwest, this also brings darkness and rain for many months and for some of us, it brings seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

Whether or not symptoms of SAD eclipse your normal disposition, there’s a good chance the sun's vacation this time of year will affect four key areas of your health.

Vitamin D

Ultraviolet rays from the sun catalyze the synthesis of vitamin D on contact in the human skin, and to a smaller degree we consume it in fish, eggs and mushrooms. This little hormone carries some big distinctions. It's been studied extensively in research for its roles in modulating the immune system, insulin sensitivity, neurotransmitter synthesis, calcium uptake and bone resorption, and may have a place in preventing devastating diseases like cancer and multiple sclerosis. The vitamin D receptor (VDR), present in almost every tissue of the body, ushers in vitamin D so it can enhance gene transcription at the vitamin D response element (VDRE) on the DNA itself to carry out these functions.

What Contributes to Lower Vitamin D Status in the Body?

Low production

With fewer daylight hours and cold temperatures, the likelihood of getting enough vitamin D from sunshine starts to diminish. For those with more melanin pigment in the skin to block out this UV catalyst, expect even lower production during this time.

Low intake

A fat-soluble vitamin, D's bioavailability depends on proper administration. Taking all fat-soluble vitamins with a meal helps get them into the body. Vitamin D-containing supplements like cod liver oil and cholecalciferol will raise circulating vitamin D levels. Tuna, mackerel, sardines and salmon also pack a vitamin D punch delivered appropriately for its solubility – as a fatty meal.

High cortisol

High cortisol and its pharmaceutical analogues are known to reduce VDR expression and thus limit vitamin D uptake and activity in the body. People who use corticosteroids or otherwise have high cortisol levels, especially during the yearly winter vitamin D famine, may want to take extra precautions to protect vitamin D status.

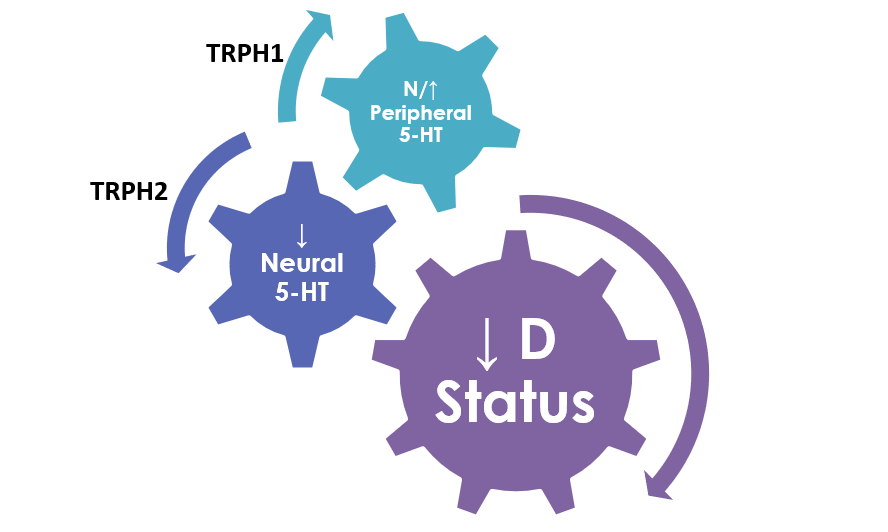

Vitamin D & the Serotonin Seesaw

If you don’t have enough vitamin D to bind VDREs, serotonin synthesis plummets and people really feel the domino effect of that drop in serotonin.

An important reason why the discussion of SAD focuses so much on vitamin D is because the VDREs present in the brain, when bound by vitamin D, act to up-regulate the synthesis of 5-HTP — the precursor to serotonin. Another important piece of the emotional wellness puzzle, serotonin acts in a variety of ways in the body – as a modulator of inflammation and the allergic response, as a signal for almost every type of immune cell imaginable, in gut function, and in the central nervous system as an inhibitory neurotransmitter that gives us emotional flexibility.

Enzymes change one molecule into another – in order to make serotonin anywhere in the body, the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase (TRPH) must transform tryptophan (an amino acid obtained from the protein we eat) into 5-HTP. 5-HTP can then be turned into serotonin by another enzyme. Because vitamin D binding to the VDREs in the brain increases the activity of the TRPH (TRPH2) enzyme there, you get more serotonin. That’s the good news. The bad news is if you don’t have enough vitamin D to bind to those VDREs, serotonin synthesis plummets and some people really feel the domino effect of that drop in serotonin.

The rest of the body feels the effects as well! In the absence of vitamin D, the activity of TRPH1 (the non-neuronal form) that is responsible for peripheral serotonin production is enhanced (in contrast to the brain TRHP2), which contributes to an exaggerated immune response, gut motility and bone resorption.

So, in effect, it acts in the complete opposite way of the TRPH2 in the brain. This is why peripheral serotonin levels measured in the urine may look normal or high while brain levels are simultaneously quite low. So, knowing Vitamin D status colors our understanding of potential serotonin levels in different compartments of the body. If vitamin D is low and there are symptoms of serotonin deficiency, it’s likely out of balance in the upstairs compartment.

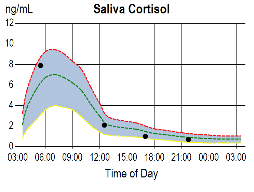

Cortisol Awakening Response

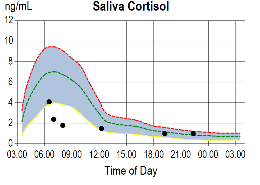

Sunlight influences the diurnal rhythm and when it becomes scarce, those rhythms can become dysregulated. The adrenal hormone, cortisol, reacts to stressors in the body like inflammation, illness and low blood sugar; however, outside of its first-response job, it follows a very typical diurnal rhythm. It can be measured upon waking and throughout the day with results in saliva that look a lot like the graph below.

Normally, in the morning as the sun begins its ascent, cortisol charts its course toward the highest level of our 24-hour day. Within 30 minutes of waking up, cortisol should continue to rise by about 50% from the waking level. When the mornings are dark, in susceptible individuals the diurnal rhythm of cortisol flattens out and it becomes difficult to shake off sleep and function normally. Another helpful measure of the HPA axis that captures that 50% rise (or absence of it) is called the cortisol awakening response (CAR) which measures cortisol in response to the “stress” of waking.

Here's a normal CAR — observe the 2nd black dot in the graph below showing the cortisol level at 30 minutes after the initial waking sample:

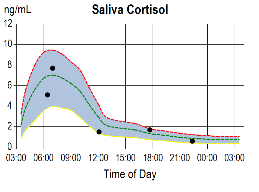

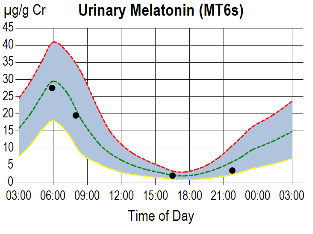

Here’s an example of a CAR in someone struggling with SAD:

Notice the morning, noon, evening and night cortisol levels are roughly within normal ranges while the attenuated CAR is the finding of interest. Overall, the defect in cortisol regulation in SAD may be missed if the CAR isn’t assessed along with the diurnal rhythm.

Altered Melatonin Rhythm

The defect in cortisol regulation in SAD may be missed if the CAR isn’t assessed along with the diurnal rhythm.

Even the absence of sunlight affects diurnal rhythms – this is where melatonin comes into play. Darkness signals the nightly melatonin flood in the central nervous system, and with darkness creeping in more and more during autumn and winter, we naturally find more and prolonged central melatonin production. There are some researchers who theorize that the increased melatonin production during the winter steals tryptophan from other parts of the brain that normally use it to build serotonin, leaving those parts of the brain at a serotonin deficit. Put this possible tryptophan-steal scenario together with a vitamin D deficiency, and it’s easy to see how a neural serotonin imbalance propagates.

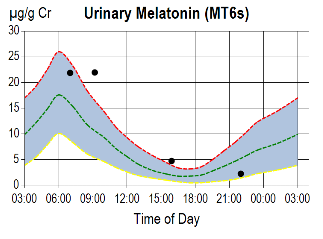

Here’s a normal diurnal melatonin curve:

Remember, in urine the first morning void contains the melatonin metabolite (MT6s) that has accumulated in the bladder during sleep, so the highest levels of the day are expected in that first morning result on the graph (as measured in ZRT's Sleep Balance profile).

Contrast that with this demonstrative example of a melatonin diurnal curve of a patient with SAD:

Notice MT6s is within the normal range (higher than median) during the night as evidenced by the level in the first morning void; but instead of dropping significantly after awakening, it remains at the overnight level. It's a groggy start to the morning with continued night-time melatonin production on board. Since this absence of light has such an effect on the body clock, natural light therapy has been studied quite a bit for helping combat SAD. It has long been used to clear out morning melatonin, stimulate cortisol production and improve mood overall.

The good news is the dark days of winter can give us a reason to turn inward, get the sleep we desperately need after a busy summer and start to the school year, and to gather up energy for the holiday season. The clocks wind back soon — are you ready?