I was so tired. I needed a new word for tired. I felt exhausted and incapacitated, utterly drained and hollowed out. It was like my brain and body were fading. And yet, these words are still not descriptive enough to relate how I felt. Getting out of bed felt grueling, punishing. I was 24 at the time, in my 4th year of my PhD program at Purdue University. I was newly engaged and so in love with my soon-to-be husband. Really good things were happening in my life. And I could barely function.

On the weekends, I slept in till noon, got out of bed to have a bite of breakfast and would go back to bed until 4 in the afternoon. I could only stay up with my fiancé for a little while in the early evenings, just to go back to bed around 8. This went on for months. At some point, he even asked me if I enjoyed my weekends and I distinctly remember saying “well of course, that’s when I get to sleep in.” During those days, he liked to tease me, saying I was the human equivalent of a sloth. [I did not find that amusing].

Not That Many Symptoms

Not That Many Symptoms

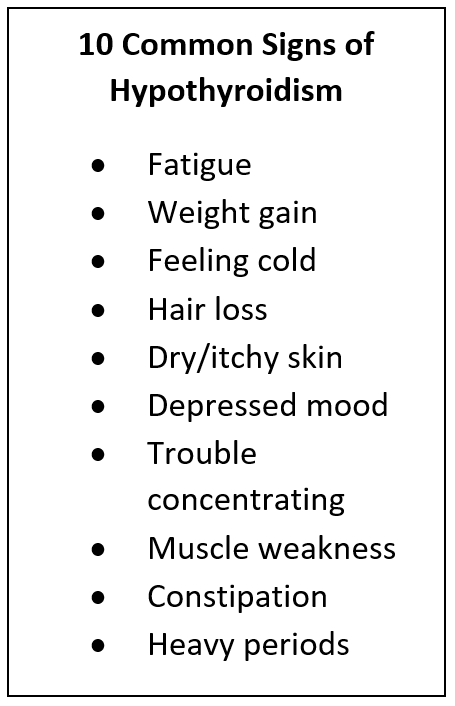

I refused to believe that there was anything actually wrong with me, after all, I was young and supposed to be healthy. I attributed my fatigue to the high demands of graduate school, rather than to something internal. Plus, my blood tests for all the typical CBC parameters were normal-ish, with the exception of mildly reduced iron stores. I didn’t have all the typical symptoms of thyroid dysfunction – I’ve always felt cold for as long as I could remember, my hair was always pretty thin and skin on the dry side. I didn’t gain weight. In fact, my “bad” lipid parameters were all on the low end, and “good” cholesterol received a whopping A++ from the student center doctor. Also, I didn’t feel that depressed. In fact, I didn’t feel much of anything, except debilitating fatigue. Eventually, I did go to the doctor once more, to say that I thought I was fine, but my fiancé wanted to spend more time with me, so he insisted that I try to figure out why I was sleeping so much.

Diagnosis

After a few additional tests, I learned that my Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) level was hovering in the mid-thirties. And so, I received my diagnosis of insufficient thyroid function called hypothyroidism. And what a difference a little bit of levothyroxine (synthetic thyroid hormone replacement) did for me! I felt like a new person!

No Known Cause

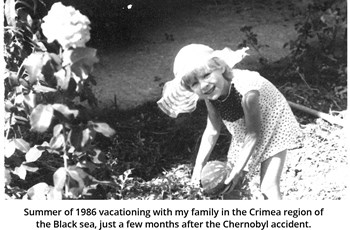

Who knows why I developed hypothyroidism. In most cases, the medical community agrees that causes of hypothyroidism are idiopathic, meaning without a known cause. In retrospect, thyroid disease is not all that uncommon for someone who grew up 200-some miles away from Chernobyl [1] or for a young woman taking birth control pills [2]. I can’t change my past. But what I can focus on right now is making sure I take levothyroxine in the morning on an empty stomach [3] and monitoring thyroid function regularly.

Laboratory Measures

Although I felt much better shortly after initiating thyroid replacement, it took me years to feel like I’ve regained that vigor or zest for life. My endocrinologist tells me that’s normal. At the time of my diagnosis, the accepted reference range for normal serum TSH went up to 10 mIU/L. For me personally, being closer to 10 meant that I would get out of bed in the morning, no problem, but I also fatigued easily, mentally and physically, not completely wiped out, but sufficiently lethargic. It took some time for my medication dosage, TSH levels and symptoms to achieve their optimal balance, where I felt best.

In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988-1994), of 17,353 people evaluated, 80.8% had a serum TSH below 2.5 mIU/L with a mean serum TSH of 1.50 mIU/L [4]. For women trying to become or already pregnant, the American Thyroid Association recommends TSH intervals to be 0.2-2.5 mIU/L [5], while other reports recommend the TSH cutoff to be less than 2.5 mIU/L to control depressive symptoms [6]. Surely enough, when I got pregnant, my levothyroxine dosage was doubled right away, and my TSH levels were monitored on a regular basis.

TSH Alone May Not Be Enough

In many cases, measuring TSH alone to diagnose hypothyroidism is not enough [7]. Free T4 and Free T3 measurements when low alongside a normal TSH may still suggest hypothyroidism [8]. Elevated thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies typically indicate autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease), a condition in which the body produces antibodies that attack the thyroid gland. The levels of these antibodies in blood can help diagnose this condition and indicate the extent of the disease. Lastly, thyroglobulin, a protein concentrated in the thyroid gland that is rich in iodine-bound tyrosine to ensure formation of thyroid hormone, can show up in the bloodstream at elevated levels when iodine status is very low [9].

Conclusions

If you suffer from the common symptoms of hypothyroidism, check your thyroid levels and talk to your doctor about thyroid hormone therapy. Even with normal levels of thyroid hormone, there are instances in which thyroid hormone activity can be affected at the molecular level by things like stress hormones or heavy metals. ZRT Laboratory offers a simple, at-home collection test from a finger-stick for thyroid parameters, where blood collected on a filter card and allowed to dry can be sent directly to us for testing of thyroid hormones.

Related Resources

- Blog: Thyroid Synthesis and Selenium: A Closer Look

- Blog: Thyroid Balance – Your Key To Brain & Body Harmony

- Webinar: Understanding Thyroid Labs

- Get Started with ZRT's Thyroid Balance Testing Today

References

[1] Zablotska LB, et al. Risk of thyroid follicular adenoma among children and adolescents in Belarus exposed to iodine-131 after the Chornobyl accident. Am J Epidemiol 2015:182:781-90.

[2] Wiegratz I, et al. Effect of four oral contraceptives on thyroid hormones, adrenal and blood pressure parameters. Contraception 2003:67:361-6.

[3] Leung AM. Levothyroxine Dosing: Morning, Night, or In Between? Medscape 2019; March 22.

[4] Hollowell JG, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), J Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 2002:87:489-499.

[5] Soldin OP, et al. The Use of TSH in Determining Thyroid Disease: How Does It Impact the Practice of Medicine in Pregnancy?, J Thyroid Res 2013 (2013):148157.

[6] Talaei A, et al. TSH cut off point based on depression in hypothyroid patients, BMC Psychiatry 2017:17:327.

[7] Ling C, et al. Does TSH Reliably Detect Hypothyroid Patients? Ann Thyroid Res 2018:4:122-125.

[8] Persani L, et al. 2018 European Thyroid Association (ETA) Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Central Hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J 2018:7:225-237.

[9] Vejbjerg P, et al. Thyroglobulin as a marker of iodine nutrition status in the general population, Eur J Endocrinol 2009:161:475-481.