Over the past few months there has been a spike in news stories related to elevated lead levels in U.S. public water systems, beginning with the crisis in Flint, Michigan. This has initiated investigations into current water testing methods and probes into violations that have been swept under the rug.

In many cases the public water supply is safe, but there's a hidden concern you need to know about – the immediate plumbing leading to drinking fountains, faucets, bathrooms, etc. in houses, apartments, schools, and workplaces could be leaching lead into the water. This can be caused by changes in water pH and temperature, additives, or the age and condition of pipes and connections.

Even though leaded gasoline, paint, and plumbing were phased out in the 1970s, they also will remain sources of lead exposure far into the future.

Children are Most at Risk

Adults absorb around 15% of lead they ingest, while children and pregnant women absorb around 50%. |

Recently, water testing in the Pacific Northwest revealed elevated levels of lead in public schools. Most schools built decades ago have ancient plumbing systems that are slowly poisoning those most susceptible to lead – CHILDREN.

This is not a localized problem, but a well understood and dangerous one across the U.S. and throughout the world. As individuals become more educated on the dangers of lead and sources of exposure, we can expect more stories to break that uncover hidden sources of lead and other toxic metals such as mercury, cadmium, and arsenic. Remember, the CDC has stated that there is no safe level of lead exposure for children.[1]

10 Need-to-Know Facts on Childhood Lead Exposure

- Childhood lead exposure is estimated to cause the US $61 billion in economic losses due to lead's neurotoxic effects leading to a decreased intelligence quotient (IQ).[2]

- Young children aged 1-5 years had average blood levels of 15 µg/dL in the 1970s, which dropped to 1.9 µg/dL in 1999, largely due to the ban on lead in gas, plumbing, and paint.[3] A blood lead level of 5 µg/dL is considered to be toxic for children.[4] Recent studies have shown that behavioral and neurological effects can occur at blood lead levels below 5 µg/dL.[5]

- In 2012, approximately 450,000 children in the US had blood lead levels above 5 µg/dL.[6]

- Adults absorb around 15% of lead they ingest while children and pregnant women absorb around 50%.[7]

- Blood transfusions can be a significant source of lead exposure in infants and young children.[8]

- Children with elevated blood lead levels may show little or no symptoms. Some of the symptoms associated with childhood lead exposure are: headache, lack of appetite, constipation, agitation, clumsiness, sleepiness, stomach pain, agitation, anemia, learning disabilities, and kidney failure.[9]

- Lead in dust and dirt is a major source of exposure for young children that are learning to crawl or walk, as it is easily consumed or inhaled.[10]

- Bone is the major target organ for lead, and because of continual bone remodeling during growth in children, lead is constantly being reintroduced into the bloodstream.[11]

- Lead affects the development of a child’s brain and nervous system, putting them at greater risk than adults.[12]

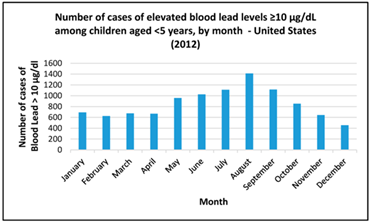

- Blood lead levels peak during dry, warmer periods of the year.[13] This is due to inhalation and ingestion of lead in dust originating primarily from prior use in gasoline.

Preventing & Detecting Lead Exposure

The half-life of lead in blood is 35 days, so it is important to test as soon as possible if you believe exposure has occurred. |

- The best way to prevent lead exposure in children is to remove them from the source. Do you know if your house has lead pipes or paint? Has your school’s water been tested recently and will they provide the method of sampling and results?

- Make sure that your child washes his or her hands prior to eating or after playing in dirt, as absorption of lead by ingestion is much higher in children than adults.

- If you have a vegetable garden or grow fruit trees, get your soil tested for heavy metals. Plants are efficient at sucking up toxins from the soil, especially metals, which will give you a good dose if eaten.

- Inside air is often much more toxic than outdoor air, because we track toxins into our home and then they stay there, getting more concentrated over time. Leave your shoes by the door so you don’t bring pollutants into your living space.

- Proper nutrition is important in reducing intestinal uptake and the damaging effects of lead. Dietary zinc and selenium have been shown to decrease absorption of, and form complexes with, lead, reducing its availability.[14] [15] Is your child consuming a healthy, nutritious diet with adequate levels of essential nutrients such as zinc, selenium, iron, and calcium?

The Take-Away

Lead is a dangerous neurotoxin and a probable human carcinogen that is most detrimental to the developing brain and nervous system of a child. It is essential to detect exposure to lead and other toxic metals as soon as possible, as there is very little that can reverse the effects of long term heavy metal exposure.

Testing blood lead levels is the most accurate and common way to determine recent and past exposure in a child. The half-life of lead in blood is 35 days, so it is important to test as soon as possible if you believe exposure has occurred.[16] Once lead enters bone, its half-life is up to 30 years.

Talk to your doctor about testing, and make sure to ask if he or she is testing lead in whole blood. Testing serum or urine is not ideal, as almost all lead is attached to hemoglobin in red blood cells.

If you're worried about needles, consider a simple finger-prick blood test that can be completed at home as an effective and less stressful alternative, especially for children.

Related Blog: "Are Heavy Metals in Lipstick Making Us Sick?"

More About Heavy Metals Element Testing

References

[1] Schnur J, John RM. Childhood lead poisoning and the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for lead exposure. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26:238-47

[2] Trasande L, Liu Y. Reducing the staggering costs of environmental disease in children, estimated at $76.6 billion in 2008. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 May;30(5):863-70.

[3] Gorospe EC, Gerstenberger SL. Atypical sources of childhood lead poisoning in the United States: a systematic review from 1966-2006. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008 Sep;46(8):728-37.

[4] CDC. Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention. Low level lead exposure harms children: a renewed call for primary prevention. CDC. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/acclpp/final_document_030712.pdf.

[5] Health Canada. Second Report on Human Biomonitoring of Environmental Chemicals in Canada; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013.

[6] "CDC Response to Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention" (PDF). http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/acclpp/cdc_response_lead_exposure_recs.pdf.

[7] Wigle DT. Child Health and the Environment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003.

[8] Gehrie E, Keiser A, Dawling S, Travis J, Strathmann FG, Booth GS. Primary prevention of pediatric lead exposure requires new approaches to transfusion screening. J Pediatr. 2013 Sep;163(3):855-9.

[9] American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Environmental Health. Lead Exposure in Children: Prevention, Detection, and Management. Policy Statement. Pediatrics. 2005; 116: 1036-1046. Affirmed Jan 2009.

[10] Woolf AD, Goldman R, Bellinger DC. Update on the clinical management of childhood lead poisoning. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007 Apr;54(2):271-94, viii.

[11] Barbosa F Jr, Tanus-Santos JE, Gerlach RF, Parsons PJ. A critical review of biomarkers used for monitoring human exposure to lead: advantages, limitations, and future needs. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Dec;113(12):1669-74.

[12] Sanders T, Liu Y, Buchner V, Tchounwou PB. Neurotoxic effects and biomarkers of lead exposure: a review. Rev Environ Health. 2009 Jan-Mar;24(1):15-45.

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) Childhood Blood Lead Levels—United States, 2007–2012. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6254a5.htm?s_cid=mm6254a5_x.

[14] Ahamed M, Singh S, Behari JR, Kumar A, Siddiqui MK. Interaction of lead with some essential trace metals in the blood of anemic children from Lucknow, India. Clin Chim Acta. 2007 Feb;377(1-2):92-7.

[15] Kargacin, B., Kostial, K., 1991. Toxic metals: In fluence of macromolecular dietary components on metabolism and toxicity. In: Rowland, I.R. (Ed.), Nutrition, toxicity, and cancer. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 197–221.

[16] Papanikolaou NC, Hatzidaki EG, Belivanis S, Tzanakakis GN, Tsatsakis AM. Lead toxicity update. A brief review. Med Sci Monit. 2005 Oct;11(10):RA329-36.