I recently had a conversation with a patient who was entering menopause and fearful of starting hormone replacement therapy (HRT) because she witnessed the decline in her mother’s health after she stopped HRT at age 65. She assumed that the decline in her mother’s health was due to the use of HRT rather than the discontinuation of it. There has been much confusion and contradiction around the use of hormone therapy for menopause since 2002 when the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) released the results of their prematurely halted hormone therapy clinical trial revealing an increase in disease parameters for women on HRT. The far-reaching effects of this trial still exist today even though a deeper look into the revelations and shortcomings of the WHI study has been published numerous times and in various publications.

After delivering a near-fatal blow to the use of HRT for menopausal women, a reshuffling of the WHI data began to tell a different story. Distinct differences in outcomes were revealed when the participants of the study were stratified by age and time since menopause. There were also differences in outcomes when comparing the use of conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) against CEE alone (1).

Now, 22 years later, a recent study published by The Journal of the Menopause Society, gathered data from 10 million senior Medicare women from 2007-2020 on the use of various forms of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) beyond the age of 65. This data was evaluated for the type, route, and dosage of HRT and its effects on all-cause mortality, breast, lung, endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancers, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, venous thromboembolism, stroke, atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, and dementia. In general, the data revealed that the use of HRT beyond the age of 65 was associated with a reduction in the above-listed diseases, but dosage, route of delivery, and the hormone formulation were key to better outcomes (2).

The science around hormone replacement therapy is still evolving and over two decades after the WHI, we have seen a major shift in the recommendations for HRT. We have gone from the fear of stroke, heart disease, and breast cancer to considering the use of HRT beyond the age of 65. So, what have we learned in the past 22 years? Before answering this question, let’s take a closer look at some of the details of the WHI hormone trial and how a reassessment of the data revealed specific details that were overlooked back in 2002.

The Women’s Health Initiative Revisited

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, a bureau within the National Institute of Health. The original study began in 1992 and consisted of three clinical trials, an observational study, and a community prevention study. Data collection for the original study was completed in 2005. Extension studies consisting of annual collection of health updates and outcomes related to heart disease and aging will be ongoing until 2026 (2).

The WHI hormone therapy trial was one of the randomized clinical trials and consisted of 27,347 postmenopausal women aged 50-79. The primary outcome of interest was coronary heart disease (CHD) because prior to the WHI, physicians prescribing HRT had believed that the use of hormone therapy could prevent CHD and other chronic diseases in post-menopausal women of all ages. Other safety and efficacy outcomes of interest were osteoporosis and breast cancer. Other measurable endpoints included stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, hip fracture, and death (1).

In the WHI hormone therapy clinical trial, 16,608 women with an intact uterus were randomized to a daily combination of oral conjugated equine estrogen (CEE, Premarin) at a dosage of 0.625 mg and oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, Provera) at a dosage of 2.5 mg or placebo. The trial of estrogen-only therapy was randomized to the 10,739 women without a uterus who received 0.625 mg of oral CEE daily or placebo. The average age of the participants was 63 years with 32.3% of the participants in the 50-59-year age range, 45.2% in the 60-69-year age range, and 22.5% in the 70-79- year age range (1).

The trial was planned for 9 years but was halted early due to an increase in disease parameters amongst the participants receiving HRT. The CEE+MPA branch of the trial was halted at 5.6 years due to an increased risk of invasive breast cancer. The CEE only branch of the trial was halted at 7.2 years due to an increased risk of stroke (1).

From that point onward, the study participants were followed observationally to evaluate the persistence of treatment effects. Most of the risks and benefits of hormone therapy dissipated within 5-7 years after discontinuation of treatment. In the CEE+MPA group, there was still a very slight increase for breast cancer but most of the cardiovascular risks waned. Positive effects included an overall reduction in risk for hip fracture and endometrial cancer. In the CEE only group, breast cancer risk continued to decline as did dementia and mortality (1).

The WHI has been a monumental undertaking that includes a large population base of postmenopausal women aged 50-79 spanning over 35 years. That’s a lot of data to work with and it will continue to provide the raw material for further analysis for years to come. However, despite the amount of data that was provided by the WHI hormone trial, it can only measure the effects of oral Premarin (CEE) and Provera (MPA) because that was the only hormone therapy given to the women in the trial. We cannot assume that these results will translate to other routes of delivery (e.g. topical, transdermal patch, vaginal, etc.), different dosages, and bioidentical hormones (e.g. estradiol and progesterone). What has been most clear upon re-evaluation of the WHI data is the timing hypothesis in which the initiation of HRT has greater benefits when started within the first ten years of menopause.

Age Stratification

In a 2020 article in The Journal of the North American Menopause Society titled “The Women’s Health Initiative Trials of Menopause Hormone Therapy: Lessons Learned,” Manson et al accessed data from a 2013 overview of 13 years of follow up with the participants, which included an age-stratified analysis. It was determined that age and time since menopause was an important differentiating factor that contributed to coronary outcomes. The women with better outcomes had started HRT closer to the onset of menopause. Starting HRT early may slow the development of atherosclerosis whereas later initiation (10 years beyond menopause) may promote inflammation and advance existing atherosclerotic plaques (1). We should also consider that age alone can be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In the WHI study, there was a 29-year spread between the youngest and the oldest participants which is nearly three decades of potential disease progression with or without HRT.

The Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE Trial) was a 6-year randomized trial of 643 healthy postmenopausal women and reported that oral estradiol (1mg/day) with or without vaginal micronized progesterone gel (45 mg/day) significantly slowed the progression of carotid atherosclerosis in women within six years of menopause but not in women more than 10 years past menopause onset. However, the increased risk of stroke, transient ischemic attack, and systemic embolism still existed in the younger group and the risk gradually increased with age (3). As noted by Goldstajn et al when comparing the effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen, there is clear evidence that oral administration of estrogens increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (4).

Premarin (CEE) vs. Estradiol

CEE is estrogen from the urine of pregnant mares and, though it is natural, eight of the ten estrogens in Premarin are not bioidentical to human estrogen. Estradiol is bioidentical estrogen and is used in both pharmaceutical and compounded formulas. Estradiol is the form of estrogen that is produced in the greatest amount by the ovaries during the reproductive years. The composition of CEE differs significantly from the estrogens found in premenopausal women and the activity of these different estrogens will vary in terms of their downstream effects on thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer progression (5, 6, 7).

Provera (MPA) vs. Progesterone

Let’s start with a definition of terms because they are often used interchangeably in the literature when discussing any form of progestogen. Progestogen is the name for the broad category that includes both synthetic and bioidentical progesterone. Progestins are synthetic forms of progesterone. Progesterone is a reproductive hormone produced naturally in the body or it can be formulated as a bioidentical hormone for HRT.

MPA is a synthetic progestin that binds with high affinity to cellular progesterone receptors, but its structure and physiologic effects are somewhat different than bioidentical progesterone and even other synthetic progestins. MPA can have effects that are quite different than the effects of bioidentical progesterone in the brain, nervous system, cardiovascular system, and breast tissue (8).

Route of Hormone Delivery – Oral or Transdermal

Premarin is an oral form of estrogen with a first pass through the liver from the digestive tract before it is delivered to target tissues. This first pass through the liver increases clotting factors that may promote thromboembolic events. In the WHI hormone trial, the CEE only group did not show an increase in breast cancer but did show an increase in ischemic stroke due to blood clots. The older a woman was at the beginning of the trial, and the longer the age since menopause, the higher the risk for stroke (1).

A 2022 systemic literature review that included 51 studies, compared the health effects of oral versus transdermal administration routes of estrogen in postmenopausal women. This study did not make the distinction between “transdermal” and “percutaneous” administration of estrogen. Transdermal estrogen application is specific to patches that deliver a higher concentration of estrogen to the blood whereas percutaneous administration is specific to the gel or spray that was included in the review. The study included estrogen therapy alone, combined-cyclic, and combined continuous dosing (combined = estrogen + progestogen) (4).

The results of the review showed that oral administration compared to transdermal and percutaneous were similar regarding bone mineral density, glucose metabolism, improvement of lipid profile, breast cancer, endometrial disease, and cardiovascular risk. However, there was clear evidence that the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) was higher with the oral administration route. The higher the dosage of oral estrogen, the greater the risk for VTE and amongst the different combinations with progestins, oral estrogen with MPA seemed to correlate with the highest risk (4).

Transdermal and percutaneous estradiol is metabolized partly in the skin and requires lower dosing than oral estrogen. This results in lower levels of serum estrone similar to premenopausal levels. Transdermal and percutaneous administration have different pharmacodynamics as compared to oral administration providing differing safety profiles related to risk of VTE especially in those who have a prothrombotic mutation like Factor V Leiden (4).

Hormone Dosage

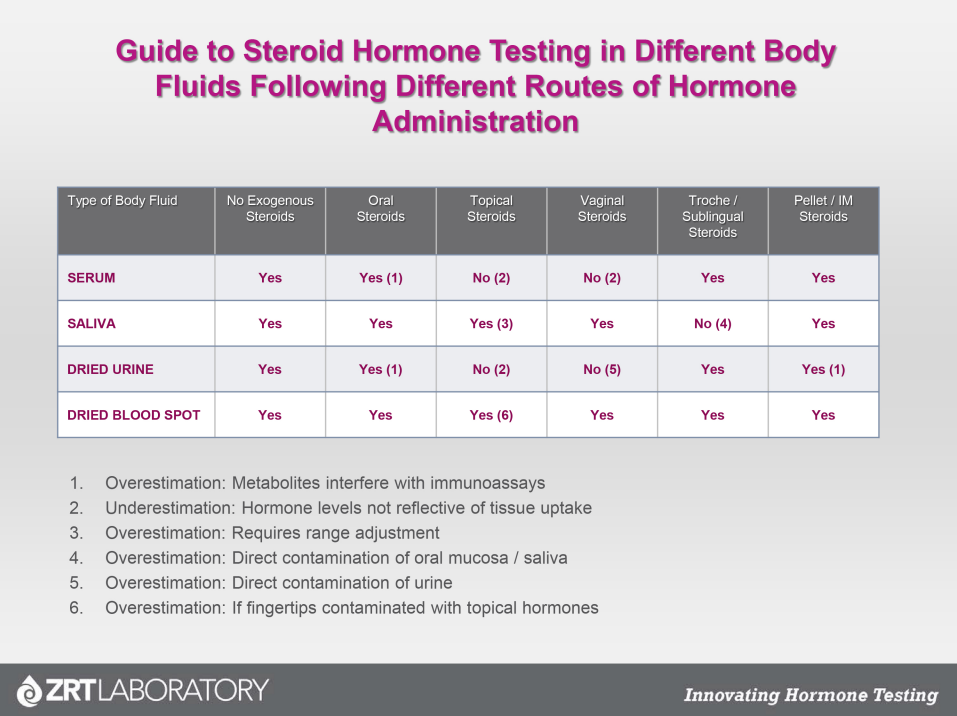

In the WHI, all women received the same dosage of hormones regardless of their age and time since menopause. We have learned over the years that a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work for every woman. The dose of Premarin (0.625 mg/day) that was used in the WHI study is considered a moderate dosage. For women who are ten or more years past menopause and have not used HRT in the past, a moderate dose of estrogen may be too much. Symptom evaluation and accurate testing can provide the feedback needed for both practitioner and patient. Methods of testing hormone levels when supplementing are also specific to the route of delivery to ensure against over or under supplementation.

Fig.1 A Guide to Steroid Hormone Testing in Different Body Fluids Following Different Routes of Hormone Administration.

As evidenced by the results of the 10 million Medicare women in the study referenced above, those who used HRT beyond the age of 65 years had the best outcomes with a low dosage. The benefits of HRT for bone density, cardiovascular health, and brain health are greatest within the first years of menopause and the benefits appear to extend beyond the age of 65 years. However, if HRT is not started within the first 10 years of menopause, higher dosages of hormones later in life cannot recapture what has already been lost (2).

So, what have we learned?

The age of the patient and time since menopause matters, the dosage of hormones matters, the route of delivery matters, and the type of hormone (CEE, synthetic, bioidentical) matters. All these parameters need to be taken into consideration when evaluating any literature on hormone replacement therapy. The study objective that reviewed the records of 10 million senior Medicare women assessed the use of menopausal hormone therapy beyond the age of 65 years and its health implications by types of estrogen/progestogens (both progestin and progesterone were evaluated), routes of delivery, and dosage. Overall, risk reduction appears to be greater with lower estrogen dosage, vaginal, transdermal or percutaneous rather oral preparations, and estradiol rather than conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) (2).

The results revealed that compared with women who never used HRT or discontinued use after age 65, the use of estrogen alone beyond age 65 was associated with significant risk reduction in mortality, breast cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, congestive heart failure, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction, and dementia. With the use of estrogen + progestin (norethindrone) there was a marginal risk reduction in endometrial and ovarian cancers, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure and venous thromboembolism. Estrogen+ (oral*) progesterone only exhibited a risk reduction in congestive heart failure (2).

A Personal Decision

In the end, a woman’s decision to use HRT is a personal health choice made between doctor and patient. Those who feel that the benefits outweigh the risks and need relief from hot flashes, night sweats, heart palpitations, insomnia, and mood issues may choose HRT. Now, with recent data showing benefits to long-term health, women may also choose to stay on HRT well into their senior years. We’ve come a long way since the 2002 results of the WHI hormone trial and the latest study by Baik et al has confirmed what many women and their doctors already knew – HRT, when appropriately prescribed, can add life to your years and years to your life.

*The route of delivery for the progesterone was not stated. This study was based on Medicare records, so it is likely that the progesterone prescribed is in the form of oral micronized progesterone (OMP) either as Prometrium or its generic equivalent.

References:

1.Manson, JoAnn E., et al. “The Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Therapy Trials: Update and Overview of Health Outcomes During the Intervention and Post-Stopping Phases.” JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 310, no. 13, Oct. 2013, pp. 1353–68. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278040.

2.Baik, Seo H., et al. “Use of Menopausal Hormone Therapy beyond Age 65 Years and Its Effects on Women’s Health Outcomes by Types, Routes, and Doses.” Menopause (New York, N.Y.), vol. 31, no. 5, May 2024, pp. 363–71. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002335. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/womens-health-initiative-whi.

3.Hodis, Howard N., et al. “Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 374, no. 13, Mar. 2016, pp. 1221–31. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1505241.

4.Goldštajn, Marina Šprem, et al. “Effects of Transdermal versus Oral Hormone Replacement Therapy in Postmenopause: A Systematic Review.” Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 307, no. 6, 2023, pp. 1727–45. PubMed Central, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35713694.

5.Bhavnani, Bhagu R., and Frank Z. Stanczyk. “Pharmacology of Conjugated Equine Estrogens: Efficacy, Safety and Mechanism of Action.” The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, vol. 142, July 2014, pp. 16–29. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.10.011.

6.Diaz-Ruano, Ana Belén, et al. “Estradiol and Estrone Have Different Biological Functions to Induce NF-κB-Driven Inflammation, EMT and Stemness in ER+ Cancer Cells.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 2, Jan. 2023, p. 1221. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021221.

7.Knowlton, A. A., and A. R. Lee. “Estrogen and the Cardiovascular System.” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 135, no. 1, July 2012, pp. 54–70. PubMed Central. Accessed 5 Aug. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007.

8.Bethea, Cynthia L. “MPA: Medroxy-Progesterone Acetate Contributes to Much Poor Advice for Women.” Endocrinology, vol. 152, no. 2, Feb. 2011, pp. 343–45. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2010-1376.