Gamma-aminobutyric acid, better known as GABA, is the neurotransmitter known for its affinity for GABA receptors throughout the central nervous system (CNS). It acts to inhibit excitatory processes – whether they be normal or pathological.

It's synthesized from the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in a process that requires vitamin B6 as a cofactor. The delicate balance in the brain between GABA and glutamate is orchestrated by shuttle systems from the Krebs Cycle, the presence of NMDA and GABA receptor modulators, enzyme cofactors, and reuptake mediators.

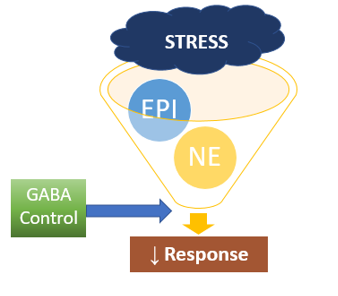

In the rest of the body, GABA plays a myriad of important protective roles. It modulates the adrenal response to stress by acting as the gate-keeper of norepinephrine and epinephrine release (catecholamines responsible for the adrenaline surge) [1]. It regulates the activity and regeneration of β-islet cells in the pancreas which are responsible for insulin secretion and blood sugar regulation [2]. GABA made and stored in the nerves of the enteric nervous system acts to mediate the upper gastrointestinal tract’s secretion and emptying mechanisms and modulate the sensation of visceral pain there. The guts are absolutely covered in GABA receptors of all types. When synthesized in the small intestine by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, GABA influences the HPA axis and up-regulates GABA receptor expression in the CNS, thanks to the vagus nerve [3]. Any imbalance in this body-wide system, whether it be in the CNS or in the periphery, may lead to sleep disturbances.

Low GABA & Sleep Problems

We see sleep disturbances not only in those with low GABA but also in those with high GABA excretion, and while the presentation may be quite similar, the underlying cause is very different. |

Applying what we know about GABA's function in the CNS and in the periphery, how do we think the absolute GABA levels we find in the urine correlate to the reported symptom of sleep disturbance? The low hanging fruit in the thought process is that low GABA levels correlate with sleep problems. Not enough inhibitory activity to get the job done – not enough brakes, so to speak, to let our busy minds absorb the halting rhythms of the day and ease into much needed rest. And in some cases, that's definitely true – for example, in the presence of oxidative stress, glutamate resources prioritize glutathione production at the expense of GABA's and leave us low in GABA, or even a simple B6 deficiency can lead to lower activity of the enzyme that turns glutamate into GABA, glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), and as a result lower GABA levels. Those with minor genetic mutations in the GAD enzyme system or those with autoantibodies against GAD may have lower GABA levels in the urine along with the symptom of disturbed sleep.

High GABA & Sleep Problems

In clinical practice though, the reality is that we see sleep disturbances reported not only in those with low GABA but also in those with high GABA excretion, and while the presentation may be quite similar, the underlying cause is really very different. Circle back to what we know about GABA’s job in the adrenal medulla as a stress modulator and it starts to make sense. GABA production and release is a reactive measure in the presence of a stressor; its release is not directly centrally mediated. In fact, it acts in an autocrine/paracrine manner when released from adrenal chromaffin cells, which live in close vicinity to the excitatory catecholamine-releasing sympathetic neurons. Without GABA's modulatory activity in the adrenal medulla, norepinephrine and epinephrine release would become a runaway train. So, this compensatory mechanism is a clue to help us get to the bottom of what’s actually disturbing sleep.

High GABA Excretion’s Link to Acute Stress

A study in 2013 [4] looked at kids with obstructive sleep apnea (hypoxia being the ultimate stressor) and found elevated overnight levels of urinary GABA, norepinephrine, and epinephrine – strengthening the idea that excessive fight or flight activity has close ties with higher GABA levels. And that extra GABA may be absolutely necessary for an individual with a ramped-up sympathetic nervous system.

The takeaway here is to assess and address the adrenal stress response first in patients with high GABA and sleep problems. Don't assume that because it’s a "good" neurotransmitter that more is better. More may actually be the smoking gun of a trigger-happy, overwhelmed sympathetic nervous system.

Related Resources

References

[1] Harada, K, et al. GABA signaling and neuroactive steroids in adrenal medullary chromaffin cells. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:100.

[2] Soltani, N, et al. GABA exerts protective and regenerative effects on islet beta cells and reverses diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108: 11692–11697.

[3] Leo, G. The gut microbiome and the brain. J Med Food. 2014; 17: 1261–1272.

[4] Kheirandish-Gozal L , et al. Urinary neurotransmitters are selectively altered in children with obstructive sleep apnea and predict cognitive morbidity. Chest. 2013;143:1576-1583.

[5] Todd, Robert D, et al. Gabapentin inhibits catecholamine release from adrenal chromaffin cells. Anesthesiology. 2012; 116: 1013–1024.

[6] Lo HS, et al. Treatment effects of gabapentin for primary insomnia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:84-90.